Why Ontology?

“If we only knew what we know, namely, in the use of certain words and concepts that are so subtle in application, we would be astonished at the treasures contained in our knowledge.” Immanuel Kant, Vienna Logic.

My interest in Ontology might be traverse to that of other people, being mainly motivated by psychology: the question I ask is – might the idea that the mind operates with an ontology help us to understand how the mind does the sorts of things that we know it does do? Other people come to Ontology from Philosophy, asking something like – what are the basic categories of reality? – or from Computer Science, asking something like – what is the best way to organize information?

To steal from Giuseppina D’Oro’s book on Collingwood, my approach is “Kantian … in so far as it seeks to uncover not the ultimate structure of reality but the presuppositions which govern our experience of the world.”

Ontology can mean many things – sometimes it seems almost synonymous with metaphysics. Here, my main interest in ontology is focused on the viability of the categories, sometimes called top-level categories, or ontological categories.

I will sketch my route via concerns with psychology to an interest in ontology.

The mind accomplishes remarkable things, and it seems to do this with recourse to generalization. A way of looking at this, is that it identifies patterns. At least one of the jobs of the mind is pattern identification.

Generalization and the identification of patterns – The mind sees similarities, or regularities, between different “things”, and then, either implicitly or explicitly, identifies certain sections of its sensory flux as being the same, and being a concept. (or, if you like, the identification of regularities IS conceptualization.)

We now have the idea that “concepts” might help us to understand the mind. It might next be useful to see whether concepts could be differentiated from each other by whether they fall into different broad categories.

It seems that they might – language often treats object concepts, e.g. “cow”, differently from property concepts, e.g. “brown”, so language might indicate a way of breaking down concepts into different categories; objects correspond to nouns, and properties correspond to adjectives. Other categories, for example relation, state, process and event, can fall under consideration in the same way.

Another approach is to analyse, logically, the different categories of concept that there may be. Aristotle and Kant are the foremost traditional thinkers on this, and contemporary approaches (see below) are taking the field forward today. It may look a bit too a priori for some, but if held to account by real-world knowledge engineering, it might provide us with useful insights.

Included in this, it might give me and people with similar interests an insight into how the brain does the mind. None of this proves that the mind has an ontology, but indicates that ontology might help us to understand how the mind does its job.

It is possible that Ontology is a wild goose chase for understanding the higher levels of the organization of the mind, but I’m yet to read anything which convincingly argues that it is likely to be so; it seems best to pursue all avenues of inquiry into the nature of our minds.

To put the argument presented here tersely assertively –

1) The mind uses concepts.

2) Concepts can be differentiated from each other, and articulated with each other, by the use of something like the Categories.

Note: The linguistic approach is fraught with dangers – for example, it is all too easy to think of noun phrases as corresponding to concrete objects, but this is often not the case. It is salutary in this regard to look down a list of most-used words in English, and to note how far down that list you have to go before you reach a genuinely concrete common noun. Similar considerations apply to other parts of speech – not all verbs are really actions, and so on. Nevertheless, the syntax / semantics interface affords insights if properly checked and treated with due caution.

Upper-Level Ontology

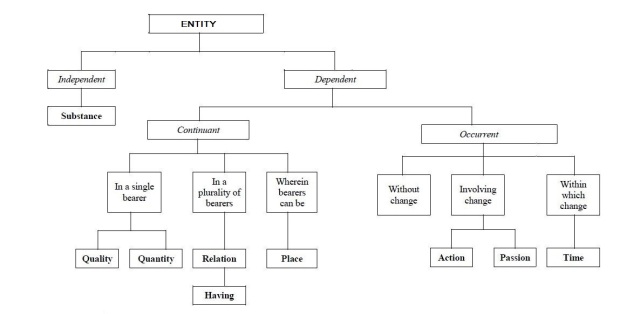

Aristotle gives the best early attempt to develop a list of the most fundamental ontological categories, now often called the top-level categories, in his work “The Categories”. He lists ten of these (emphasis added) –

“CHAPTER 4

1b25. Of things said without any combination, each signifies either substance or quantity or qualification or a relative or where or when or being-in-a-position or having or doing or being-affected. To give a rough idea, examples of substance are man, horse; of quantity: four-foot, five-foot; of qualification: white, grammatical; of a relative: double, half, larger; of where: in the Lyceum, in the market-place; of when: yesterday, last-year; of being-in-a-position: is-lying, is-sitting; of having: has-shoes-on, has-armour-on; of doing: cutting, burning; of being-affected: being-cut, being burned.”

The diagram above is a fairly traditional way of setting the categories in order (I leave it to my dear reader to spot which of Aristotle’s categories in the quotation has gone walkabouts from the diagram!) It indicates a major division between: substances, which are independent, that is, not dependent for their existence on something else, and: all the other categories, which are dependent – on substances. Thus, the redness (a quality) of the apple depends on the apple (a substance).

All of these top-level categories are what are known as universals. They are not, however, the only universals – lower-level universals would be such terms as “dog”, and so on. I will leave open for now the important question of just how “top” a top-level category need be.

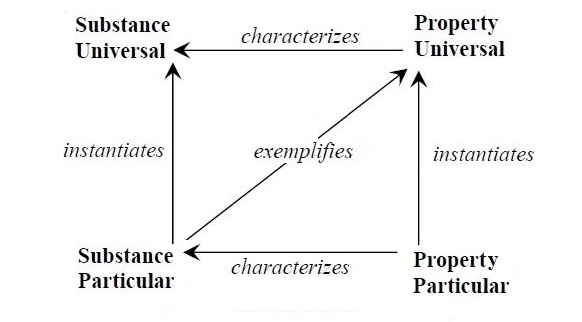

Beside universals, our main concern, we need some other ideas to show how ontology locks on to reality. As well as universals, such as “dog”, we need the concept of particulars, such as Boz, my family’s dog. Boz is a particular, and instantiates the universal of dog. Regarding this instantiation, we can say he is an instance of the universal dog. Dog is itself, in terms of Aristotle’s top-level categories, a substance. The diagram at the start of this article, derived from the work of E. J. Lowe, indicates the relationship between universal and particular (sometimes also called individual). It also indicates the relationship between substance and property (property is a near synonym for quality, or qualification in the Aristotle quotation above) and sort of shows how the four terms thus generated might work together. Substance and property are very important top-level categories.

There are a few more insights from Aristotle which are important for us. Regarding the “is a kind of” relationship, higher universals subsume lower – dog is a kind of mammal, mammal is a kind of animal, animal is a kind of living thing, and living thing is a kind of substance. The relationship between higher and lower terms such as mammal and dog is expressed, relationally, by calling them genus and species respectively. (Note that for the Linnean taxonomy, as used by biologists to classify living things, genus and species have more specialized meanings, as two particular levels amongst others). This relationship gives us the terms generalization (very important) and specialization (or specification). Other useful terms for such higher / lower relationships are superordinate / subordinate.

A species falls under a genus, and inherits its qualities, properties, etc. All that is true of a higher universal is true of any lower universal which it subsumes. But any species is also differentiated from other species that fall under the same genus. This is called its differentia. For a species, its genus together with its differentia define it:

genus + differentia = species.

The taxonomy of ontological categories, like other taxonomies, is hierarchical, having a tree-like structure, and can be perspicuously represented by tree-like diagrams. A tree, in this sense, is, mathematically, a kind of graph. Wikipedia has – “In mathematics, and more specifically in graph theory, a tree is an undirected graph in which any two vertices are connected by exactly one path. In other words, any acyclic connected graph is a tree.” [for now, I quibble “an undirected”, since I think a tree of ontological categories needs to be directed. I would suggest “an either undirected or directed”]

Some additional ideas I should at least mention, though at the risk of terminological overload, (the field of ontology just IS a terminological nightmare!), are –

- Class and Set – Many of the “things” we’ve been considering here are classes: a universal is a kind of class. Class is, however, a wider term than universal, category, etc., and is often used in approaches such as UML. Class involves few ontological commitments. Classes are usually defined by singly necessary and jointly sufficient conditions, and the idea of genus and differentia explained above with reference to universals is a restricted version of this. Set is a term which has perhaps an even wider application than class. Sort and sortal also belong here, and, indeed, kind. (Note also type and token)

- Dependence – I’ve already mentioned this, but it will be as well to repeat here, bringing in some related terms: properties or qualities, (usage varies), depend upon substantial entities, paradigmatically substances (also known as objects). Substances are independent entities. Properties or qualities are dependent entities. Characterization and exemplification are related terms: a property characterizes a substance, and conversely, a substance exemplifies a property. The property of an object is thus a characteristic, and an object is an example of a property.

- Essence and Accident – These, and their adjectival forms essential and accidental, usually refer to two different kinds of property – respectively, those which are necessary for a thing to be the kind of thing it is, and those which are not, being perhaps temporary states. Though usually properties, perhaps the distinction could also apply to parts, and other terms in an ontology.

- Attribute and Mode – For properties, a distinction is sometimes made between attribute, often regarded as a synonym for property, and mode. Lowe regards property universals as attributes, and property particulars as modes. Here seems the best place to mention another conundrum – is it colour that is a property, or is it red that is a property? Some computerese has red as a value of the property colour, and this or some similar distinction of terms seems necessary.

- Object and Stuff – Both these terms are close to that of substance, with object perhaps a synonym for substance. As in grammar, a distinction can be made between objects, or things in common parlance, and stuff. It is the difference between dog and water. Grammarians should think of countable and uncountable nouns, and number and measure. Discrete and continuous is a related duality.

- Whole and Part – (consideration of which is often termed Mereology, Meronomy, and sometimes Partonomy) – Both whole and part are substantial or processual entities, and a whole made of parts can also be a part of a larger whole; whole and part, like genus and species, are relational concepts, so often don’t appear in taxonomies as entities in their own right. However, the whole-part relationship is very important within ontology. It, too, like a taxonomy, has a hierarchical, tree-like structure, termed meronomy. Composition and composite are very much to do with wholes and parts, and can be contrasted with aggregation and aggregate, an important category. Note also the term component: a part of a composition or composite.

- Continuant and Occurrent – Continuants are the sorts of things we have already considered – such as objects and qualities. Occurrents bring in the more dynamic entities of reality – such as processes and events. Nearly synomymous terms are endurant and perdurant.

- State – States seem to me to be non-essential properties or qualities. Non-essential in this sense is sometimes called accidental, and non-essential properties or qualities are accidents. However, states are also often put on the dynamic, “occurrent” side of things, along with processes and events.

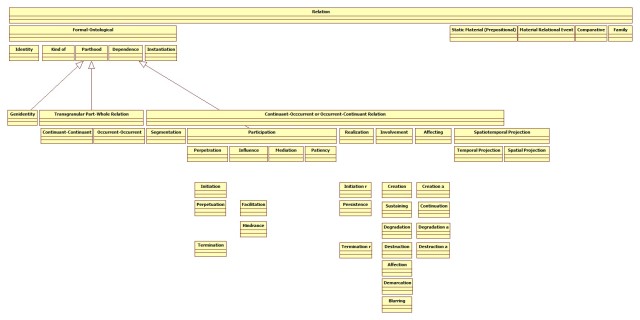

- Relation – Relations are in many ways of great concern to me. There are some attempts at taxonomies of relations below. Relation covers a wide range, and its analysis is very difficult. Note particularly that “Relational Quality” can be regarded as an entity, rather than as a relation.

A Detour Through Kant

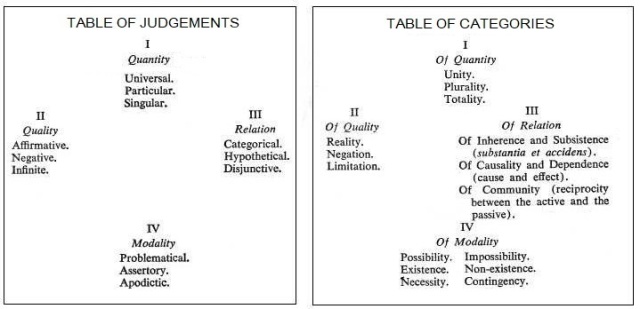

Immanuel Kant, one of the most influential thinkers in the history of philosophy, was dissatisfied with Aristotle’s treatment of the categories, which he regarded as being a congeries, lacking any real structure. Kant, a sort of super-systematizer, tried to tidy up the categories into a table with a 4 x 3 structure, rendering 12 categories, which have similarities to and differences from Aristotle’s 10 categories. An interesting aspect of this, displayed in the tables below, is that Kant saw an isomorphism between the organization of judgements, which we would now regard as the province of formal logic, also with a 4 x 3 structure, and that of the categories: the categories are founded in the nature of reason.

All of the terms in both of these tables are held together by the unity of consciousness, or, in Kantian parlance, “the transcendental unity of apperception”. I have neither the time nor the intellectual confidence to explore these ideas properly, but include them here to indicate intriguing possibilities. Curious readers can look elsewhere for more adequate expositions.

Contemporary Approaches

There are contemporary approaches to ontology which attempt to refine and formalize some of the considerations given above. Notably, there’s –

BFO, Sowa, (for these two, see below),

GFO, UFO, Yamato, Proton – and there are still more!

For Cyc, arguably the daddy of them all, see also its Wikipedia article, where it is described as the world’s longest-lived artificial intelligence project, and regarded as one of the most controversial endeavours in the history of artificial intelligence.

I will now give a little more detail on two of these contemporary approaches.

Basic Formal Ontology

Basic Formal Ontology, developed by Barry Smith et al, is a present-day endeavour in the field of ontology. Their approach, for me, makes sense and shows promise. I recommend a glance at their literature, as it gives an idea of what contemporary work on ontology looks like. The websites for the project are at –

http://basic-formal-ontology.org/

and http://ontology.buffalo.edu/smith/

and the best reference work seems to be – “Building Ontologies With Basic Formal Ontology” by Arp, Smith and Spear.

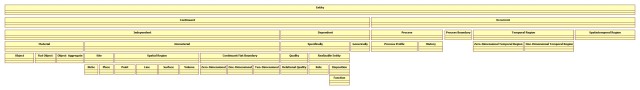

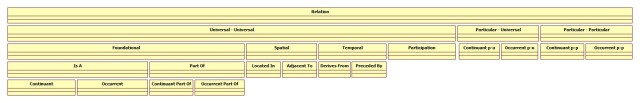

The diagrams below (click on them for higher resolution) are my own interpretation of their project. Since there is little point in my regurgitating their own materials when the reader can consult the sources directly, the diagrams serve as my own terse summary. Note, however, that none of these diagrams should be directly attributed to the BFO project – I am not part of it, so the diagrams are not canonical or authoritative. The asterisked diagrams are based on older versions of BFO. The second Relations diagram, asterisked, in particular might have been superseded, but it is suggestive of matters left out of later developments. It is based on the paper “The Cornucopia of Formal-Ontological Relations” by Smith and Grenon, which may have been quite speculative and conjectural in the first place. Given all these provisos, I have nevertheless tried to be faithful to the work of the BFO group, and hope I have not been fanciful or, indeed, unduly original.

Entities

Entities*

Relations

Relations*

Smith et al do not regard their project as psychologistic, so do not present their categories as pointing to concepts, that is, as illuminating how the mind works, but rather directly realist, referring to reality. They are also very concerned with the Computer Science orientation, though with a sophisticated background knowledge of philosophical matters, and are directly involved in developing computer systems. They see ontology as being vital to enhancing the interoperability of databases, and thus helping to make scientific advance more efficient and more swift.

Smith et al give good reasons for their referential position, and though my own approach is motivated by cognitive or conceptualist concerns, based perhaps on sense rather than reference, as long as there is a general convergence we need not worry too much. Since within epistemology my position is realist, my Kantianism is, in this regard, attenuated. Ultimately, I regard categories, schemata, frames, etc. as enabling us to know and to navigate the world – they work, at least enough of the time, because they help us to identify patterns and regularities which are real. How this has come about is explicable by recourse to Darwinian evolutionary theory. Pre-Darwinian philosophers like Aristotle and Kant could not, of course, avail themselves of the insights afforded by such an approach to epistemology. Konrad Lorenz observes, somewhere, that what for Kant is a priori, is, from the point of view of an evolutionist, a posteriori. Given this, it is reasonable to follow Smith et al’s realism rather than conceptualism, not the least reason being that it helps keep ontologies consistent, and helps avoid some of the gobbledegook they have identified in efforts which muddle realist terms with conceptualist terms.

Related to this matter, note that in this article I have rode roughshod over use / mention distinctions: I have often ignored the need to put quotation marks around terms, and so on. For my purposes now, such considerations would be a distraction, and would amount to clutter.

As something of a side issue, I am sceptical of the aims of Smith et al to impose a logical / ontological language on scientific researchers. It seems to me that this would be to demand of researchers that, as well as presenting their findings, they should fulfil the additional task of translating their findings into the latest ontologese, a double burden. Perhaps we simply need to accept the likelihood of a time-lag between cutting-edge research and the tidying up of any viable results into the ontology.

Sowa

Another approach to ontology can be found in the work of John Sowa and his team on knowledge representation, the KR Ontology. The website for the project, which is very well organized and extremely detailed, can be found at –

http://www.jfsowa.com/ontology/index.htm

and the core book is – “Knowledge Representation: Logical, Philosophical, and Computational Foundations” by Sowa.

Like Smith, Sowa is very knowledgeable of philosophy and its history, and indeed, this may be part of the attractiveness to me of their approaches over more merely computer-based orientations.

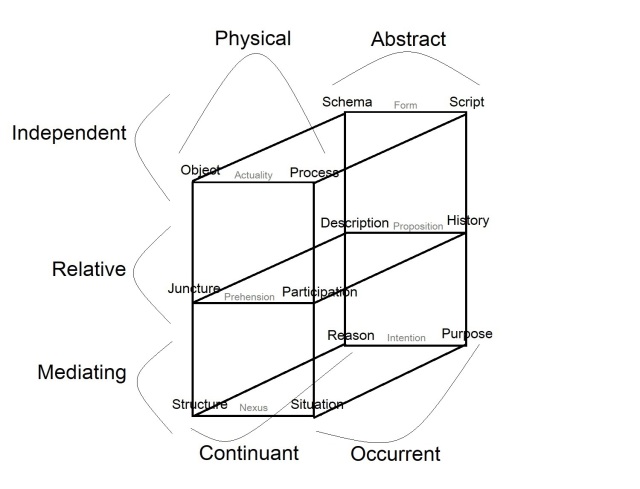

The diagram below, taken directly from Sowa, represents Sowa’s top-level ontology.

In the following diagram, I have arranged Sowa’s categories to show their “dimensional” structure.

Sowa takes very seriously Peirce’s trichotomy of firstness, secondness, and thirdness, which are, in the diagrams, Independent, Relative, and Mediating, respectively:

“First is the conception of being or existing independent of anything else. Second is the conception of being relative to, the conception of reaction with, something else. Third is the conception of mediation, whereby a first and second are brought into relation.” Peirce – The Architecture of Theories, quoted in Sowa – Knowledge Representation

The terms Actuality, Prehension, and Nexus, also in the diagrams, are owed to the influence of Whitehead, who was also partial to a threesome. Peirce and Whitehead are very important to Sowa’s thought.

If I understand Sowa correctly, his trichotomous approach can be traced back, via Peirce, to Kant. Recall Kant’s two tables, each with a 4 x 3 structure – the 3 here provided Peirce with inspiration. The resemblance can be seen most clearly in the triple under “Of Relation” in the Table of Categories (see above). Some readers might be reminded of Hegel and dialectics, also following from Kant.

Ontology Walking On The Wild Side

“Basically, the common people double a deed; when they see lightning, they make a doing-a-deed out of it: they posit the same event, first as cause and then as its effect. The scientists do no better when they say ‘force moves, force causes’ and such like, – all our science, in spite of its coolness and freedom from emotion, still stands exposed to the seduction of language and has not rid itself of the changelings foisted upon it, the ‘subjects’” Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality

The mainstream of western philosophy tends to have an orientation towards objects – objects and their properties are a central concern. Most of this article takes such an orientation for granted, in a fairly unquestioning way. However, there are those who rebel against this orientation, and who form what we might think of as an underground of potentially subversive discontents. We can trace this counterculture back to Heraclitus, and his famous comment that “you could not step twice into the same river”, which was actually only Plato’s gloss – what Heraclitus actually said was “On those stepping into rivers staying the same other and other waters flow”, which is rather more nuanced. Heraclitus is the locus classicus of “everything flows”, that all is in a constant flux, and he takes fire, in its protean activity, as the fundamental reality.

Alfred North Whitehead develops a modern (twentieth century) process philosophy, which quite consciously tries to budge the usual assumptions of both the venerable mainstream, and our normal everyday ways of thinking. This involves of necessity many unusual uses of words, neologisms and near neologisms. He is a peculiar character in the philosophical pantheon; Whitehead, with Bertrand Russell, wrote the Principia Mathematica, an extremely difficult work of mathematical logic which stands near the beginning of modern analytical philosophy, and this alone should indicate that he was a man of formidable intellect. His subsequent work seems like something of an about-face, a complete rejection of the atomistic approach he had helped to found. His main work of this later period is “Process and Reality”. Russell and Whitehead remained lifelong friends, but Russell comments, in his autobiography, on Whitehead’s later ideas thus –

“His philosophy was very obscure, and there was much in it that I never succeeded in understanding. He had always had a leaning towards Kant, of whom I thought ill, and when he began to develop his own philosophy he was considerably influenced by Bergson. He was impressed by the aspect of unity in the universe, and considered that it is only through this aspect that scientific inferences can be justified. My temperament led me in the opposite direction, but I doubt whether pure reason could have decided which of us was more nearly in the right.”

If Russell finds something very obscure, and fails to understand much of it, one wonders what hope there is for the rest of us. Something brought out by this quotation is a link between the attractions of a dynamic, process- or event-based approach, and an intuition of the unity of the universe, now often termed holism. “Object” as a concept seems rudely recalcitrant to the flow and the unity, and perhaps something of a party-pooper. Many of these considerations bear a relation to dialectics, a topic which I address elsewhere.

But let us highlight a word in the phrase with which this section began, and which might otherwise pass unmarked – “The mainstream of western philosophy”. Eastern thought – including hinduism, buddhism, tao, etc. – often emphasizes the ultimate fluidity (and unity) of reality, taking the view that all is impermanence and that separable objects are only appearances within the world of samsara, the world of illusion, and are at best mere abstractions from the primary flux.

To summarize and conclude this section, we have here noted the presence of a loose school of thought which privileges dynamic, occurrent terms over continuant terms – it privileges terms like process, event, etc. I think my own attempt in another article to advance a relationalist metaphysics, though it is not temporal and dynamic, has a connection.

Where Has The Mind Gone?

This article began with a declaration of my psychologistic orientation, but little of the material above gives any place for mental terms as such: the mind might have an ontology, but if so, surely a social being would have in its repertoire of ontological categories those which are of, or involve, other mental entities, such as persons?

[Under Construction] To get across the idea of ontology in its basics, I have restricted myself to fairly “mindless” terms. The key term with which a lot of ontology grounds its … address the mind-like aspects of the world is “agent”. From this, lots of other terms follow – intentionality – propositional attitudes – believes that and desires that … social ontology – Searle

Conclusion

[Under construction – categories in reality – categories in the mind – mind as pattern / regularity identifier – granularity / resolution both spatial and temporal (e.g. objects as events) – perspectives, especially the continuant / occurrent perspectives – purposes – provisional position – flexibility to the application of the main categories – ontology and creativity]

This is excelent!

Thanks, Daniel. It’s about as far as I got over a year ago.