In Hegel and Revolution, the authors Terry Sullivan and Donny Gluckstein focus on the aspects of Hegel’s thought which are likely to be of most interest and use to marxists, and this is understandable given that they are marxists writing for an activist audience, and that outside academia, it is Hegel’s influence on Marx and the marxist tradition which has been most important. However, on the whole they are fairly succesful in not painting over Hegel’s contours with marxism in such a way as to obliterate them. Here, I will take their work as a base, give some critical comments, but explore other aspects of the Hegel-Marx connection. This article is a companion piece to my article Dialectics.

The three core topics Sullivan and Gluckstein address are alienation, the philosophy of history, and dialectics, so we will begin with them.

Alienation

The concept of alienation is certainly one of Hegel’s ideas that had a massive impact on Marx and subsequent marxists, but I do not believe that it is central to Hegel’s thought on his own terms. It features in, but in no way dominates, the Phenomenology of Spirit, and receives a handful of mentions in his mature work, the Philosophy of Mind. But given the focus of Sullivan and Gluckstein, it quite reasonably has a prominent place; its significance to the early Marx achieving lift-off is immense. They deal well with Marx’s debt to and differences from Hegel regarding alienation.

A mention of Marx’s four-fold breakdown of alienation would have been good. It is found in the early work, the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, and, condensed, is

(1) The relation of the worker to the product of labor as an alien object exercising power over him. This relation is at the same time the relation to the sensuous external world, to the objects of nature as an alien world antagonistically opposed to him.

(2) The relation of labor to the act of production within the labor process.

(3) Man’s species being, both nature and his spiritual species property, into a being alien to him, into a means to his individual existence. It estranges man’s own body from him, as it does external nature and his spiritual essence, his human being.

(4) An immediate consequence of the fact that man is estranged from the product of his labor, from his life-activity, from his species being is the estrangement of man from man.

I have always found (1) and (2) congenial, and readily assimilable to the later concept of exploitation, but (3) and (4) somewhat obscure. However, I have recently come to give some recognition to (3) – if man’s species being is conscious practice, then his loss of control over such practice is a knife to the heart of his very being. I still have trouble with (4), but if we take intra-species cooperation as more fundamental to our nature and conscious practice than competition, it may be valid.

More generally, alienation captures, in a way the concept of exploitation doesn’t, the consequent loss of the entire human world to man, for example in the way his surroundings in most of the built environment around him are not under his control.

History

Hegel is quite rightly seen as one of the most historically aware of the great philosophers, but I believe there are aspects of the dynamism of his thought which are not really historical. His Logic is dynamic, with each category, owing to its inadequacy, passing over into another until we reach the final, all-embracing Idea. But the dynamism of the Logic cannot be that of history, and is not even temporal, since it takes place outside space and time. Of the Logic, Hegel remarks,

“It can therefore be said that this content is the exposition of God as he is in his eternal essence before the creation of nature and a finite mind.”

Hegel’s Philosophy of History was published late, indeed posthumously, and is a collection of his lecture notes and the notes of those present at the lectures existing in different versions and translations. Although Hegel did not publish a book devoted to the philosophy of history, the materials we have are deemed accurate to his thought by experts. Hegel took his lecture series very seriously, and put a great deal of work into their preparation, similar to that for his books.

There is a difficulty with his philosophy of history, in that it does not sit easily into the framework shown by the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, with its threefold division into the Logic, the Philosophy of Nature, and the Philosophy of Mind. In some ways, the Philosophy of History cuts across the edifice of his established structure.

Within Sullivan and Gluckstein’s presentation of Hegel’s Philosophy of History they maintain that “Hegel is not an idealist in the sense of holding that everything existed as ideas. However, we do think that he is an idealist in a weaker sense. And this sense is that whilst he readily accepts that the physical and material world exists – the world of tables, trees and i-Phones – for Hegel the driving force of history is not the material world but rather ideas and, in particular, reason.” They further note that “Hegel remains the most curious idealist for in the Introduction not only does he talk about social class but he also acknowledges that the very climate of the earth affects the development of freedom.”

However, I would maintain that Hegel is indeed an idealist – an absolute idealist, or objective idealist.

What I think creates some confusion is if the threefold division of the Encyclopedia is not held in mind – Hegel has a place for nature in the whole of the second volume, and nature is second in the true Hegelian sense. Many are unhappy with the way the absolute idea, concluding the Logic, then mysteriously generates nature, but that is the way Hegel has it. (As for the status of artifacts such as tables and chairs in Hegel’s system, I don’t know, but I’ll assume they have something of nature in them. It is also notable that Sullivan and Gluckstein see social class as unproblematically material, but that’s marxism for you). And after nature comes mind, culminating in absolute mind, or absolute spirit. Hegel seems to recognize the involvement af nature as well as mind within history, perhaps with nature more dominant in history’s earlier stages and mind in its later stages.

It is only if one takes idealism to mean an absolute denial of the reality of physical things that the label of idealist could be withheld from Hegel. As Hegel himself says, in the Science of Logic,

“Every philosophy is essentially an idealism or at least has idealism for its principle, and the question then is only how far this principle is actually carried out.”

There is an issue which Sullivan and Gluckstein deal with in their chapter on Dialectics, but which seems to me as easily to fit within their consideration of Hegel’s and Marx’s Philosophy of History. It is the issue of necessity, closely related to that of determinism. They note that “… Hegel held that the nature of categories forces them to pass into their opposite and onto a new, higher category as a matter of necessity …” The categories here seem to be those of the Logic, which as I have already noted, though dynamic, are not really historical, though something like this dynamic pervades Hegel’s system as a whole. But to contrast Hegel and Marx, they then draw attention to some famous lines of a historical nature from the Manifesto of the Communist Party –

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.”

The part of the quotation in italics is the most important for us here.

Thus for Sullivan and Gluckstein, Hegel saw things as displaying necessity, a unidirectional movement, but Marx saw how contradictions are resolved as involving contingency, and as not being predetermined. “Rather, their resolution was dependent on other things, in particular how the struggle between classes was fought, won and lost.” What I wish to note here is that though Sullivan and Gluckstein talk of contingeny, they do not mention the possibility of multiple possible outcomes, but simply replace Hegel’s unidirectionality with a bidirectionality, one direction good, a sublation, the other bad, a mere destruction.

They seem to be having their Hegelian cake and eating it. Such a binary way of looking at things is echoed in the stark alternatives of Rosa Luxemburg’s (or possibly Karl Kautsky’s) phrase “socialism or barbarism”. Now, I don’t wish to deny that some options, especially political ones at the present juncture, might be as indicated, but rather to indicate that the basis in dialectics for such a line of thought involves hidden assumptions, or perhaps that dialectics itself might need some reworking.

Dialectics

Sullivan and Gluckstein’s treatment of dialectics is good, especially considering that it is a notoriously difficult subject, and that they subsequently downplay the Logic and, relatedly, recent concern with the influence of Hegel’s Logic on Marx’s method or conceptual construction.

They make the notable point that Hegel sees his Logic as a logic, rather than some sort of metaphysics, or an ontology, because it is driven by necessity, and necessity is one of the hallmarks of logic. I tend to think of Hegel’s Logic as a metaphysics or an ontology rather than a logic, but Hegel and Revolution here draws attention to a pertinent point.

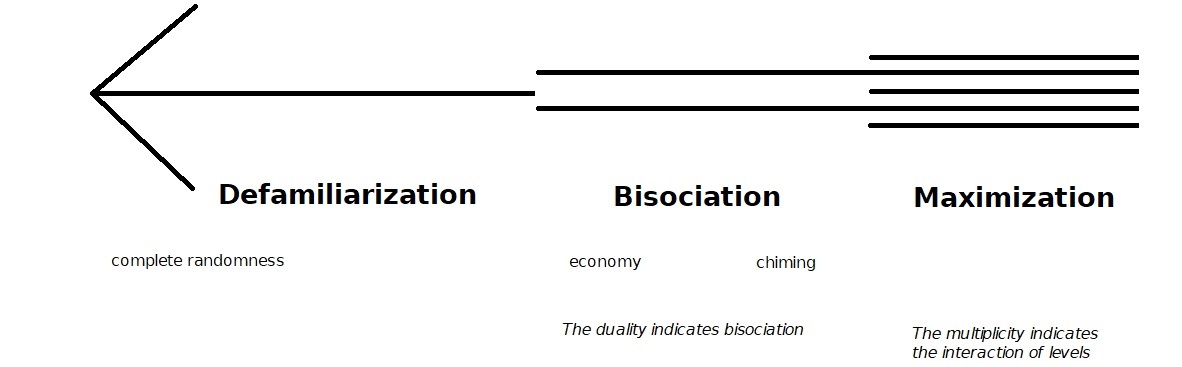

Sullivan and Gluckstein also give a good, though brief, account of the core of Hegel’s dialectical movement. I take the liberty of diagramming it my own way thus –

The base of the triangle would seem to represent negation.

Two concepts which should find a place on this diagram, either on a vertex or an edge, are sublation, and negation of the negation. They may well be synonymous. They seem to me to be labels for the dashed arrow on the left, or perhaps sublation is the dashed arrow on the left, and the negation of the negation the arrow on the right. But that’s until someone persuades me otherwise…

[I should, at this point, say more about determinate negation, using Charles Taylor and Michael Rosen, and John W. Burbidge on the to-an-fro becoming a new concept]

But the authors are clearly happier with matters such as alienation, history, and the state, than with concern for Hegel’s logic and Marx’s method.

They seem to put this as an either / or, but surely an adequate treatment would cover both (as indicated, their treatment of the dark arts of Hegelian logic, though brief, is quite good). They downplay the significance of Hegel’s Logic in their Conclusion, but it is the foundation of his mature system, and takes up 1 and 1/3 of the 4 books he published as such, or, if you divide the Encyclopedia into 3 books, 2 of his 6 books are concerned with Logic, and it has priority within the sequence in the Encyclopedia.

But perhaps the quest to hunt down the Hegelian elements within Marx’s method is somewhat chimerical and has got out of hand. Nevertheless, I will here set “Hegel and Revolution” aside and mention some aspects of this.

Totality (and the understanding and reason)

Marx seems to follow Hegel in his conception of what properly theoretical work should consist in, or what its results should look like – a system or totality with the least arbitrariness to it, and the highest level of integration or integrity that its subject matter allows. This sort of integrity is what reason achieves, and the lack of such real integrity is displayed in work of a lower level, that which is a result of the mere understanding, exemplified by those whom Marx called the “vulgar economists”, who earned his scorn.

To put the matter in terms of method, the understanding will grasp its subject matter as being made up of a bunch of different “things”, which it will, as well as it can, get into some sort of an order. But reason will find a necessity to the inter-relation of these different “things”, and the more the subject area does indeed have a unity, the better it will be able to do so.

However, outside our theories, just how much anything, even everything, really does form a totality, I will leave open.

Opposition

To indicate the sorts of oppositions which can be seen to structure Marx’s Capital, the following diagram from David Harvey’s A Companion to Marx’s Capital looks useful. However, I am not competent to assess it properly, or analyze its Hegelianism or lack of Hegelianism.

Levels of Abstraction

[movement between theory and data?]

Hegel and me

It is the grandeur of Hegel’s vision which I find most inspiring. He builds a system in which so many things are given a place, and it is the integration, the focus on the totality and the unwillingness to give the arbitrary too much room, which exemplify a certain kind of philosophy.

Regarding his mechanism of contradiction, opposition, negation, I think that impulse is more one from my nature than from Hegelian influence – I am a dialectical thinker, who will always look around for what is falling outside the system, but with a desire thus to widen the system. But it has to be done in an honest way. And there are dangers to The System. Any system.

Hegel and Marx – A Comparative Checklist

Contradiction

_____Hegel

_____Marx

For Marx, contradictions can be latent, but when they become manifest, express themselves as crises.

The primary contradiction within capitalism is that between the relations of production and the forces of production. This generates class struggle.

The Marx Dictionary, by Ian Fraser and Lawrence Wilde, gives an able summary of Marx’s use of the term contradiction (emphasis and segmentation added) –

__________Grundrisse

“In the chapter on money in the Grundrisse (1857-1858), when

examining the relationship between money and commodities, Marx specifies

four contradictions that are present.

He begins with the contradiction within the commodity between the particular nature of the commodity as a product, or its use value, and its general nature as exchange value, expressed in money.

The other contradictions involve the separation of purchase and sale by space and time,

the splitting of exchange into mutually independent acts

and the twofold nature of money as a general commodity to facilitate exchange and a particular commodity subject to its own particular conditions of exchange.”

__________Capital III

Fraser and Wilde also observe that “Marx’s exposure of the contradictions of capitalism is completed in Capital 3 (1864-1865), particularly in his discussion of the tendency of

the rate of profit to fall and its implications. For Marx, the desperate race for profit drives the system to more volatile and precarious competition, but it is always running against the problem of finding effective demand. Capitalists need low labour costs to make their profits, but they need consumers with money to buy their goods. This can lead to situations in which over-capacity of production goes hand in hand with unemployment.”

Negation

_____Hegel

_____Marx

Unity of Opposites

_____Hegel

__________Logic II Essence

__________determinations of reflection – identity, difference and opposition

_____Marx

__________Capital I

__________unities of use-value and value (and see the diagram above, under the heading “Opposition”, for an indication of what a fuller treatment might look like).

Quantity into Quality

_____Hegel

__________Logic I Being – Measure

“It is said, natura non facit saltum; and ordinary thinking when it has to grasp a coming-to-be or a ceasing-to-be, fancies it has done so by representing it as a gradual emergence or disappearance. But we have seen that the alterations of being in general are not only the transition of one magnitude into another, but a transition from quality into quantity and vice versa, a becoming-other which is an interruption of gradualness and the production of something qualitatively different from the reality which preceded it. Water, in cooling, does not gradually harden as if it thickened like porridge, gradually solidifying until it reached the consistency of ice; it suddenly solidifies, all at once. It can remain quite fluid even at freezing point if it is standing undisturbed, and then a slight shock will bring it into the solid state.”

_____Marx

__________Capital I

“A certain stage of capitalist production necessitates that the capitalist be able to devote the whole of the time during which he functions as a capitalist, i.e., as personified capital, to the appropriation and therefore control of the labour of others, and to the selling of the products of this labour. The guilds of the middle ages therefore tried to prevent by force the transformation of the master of a trade into a capitalist, by limiting the number of labourers that could be employed by one master within a very small maximum. The possessor of money or commodities actually turns into a capitalist in such cases only where the minimum sum advanced for production greatly exceeds the maximum of the middle ages. Here, as in natural science, is shown the correctness of the law discovered by Hegel (in his “Logic”), that merely quantitative differences beyond a certain point pass into qualitative changes.”

Negation of the Negation (Sublation?)

_____Marx

__________Capital I Chapter 32

“The capitalist mode of appropriation, the result of the capitalist mode of production, produces capitalist private property. This is the first negation of individual private property, as founded on the labour of the proprietor. But capitalist production begets, with the inexorability of a law of Nature, its own negation. It is the negation of negation. This does not re-establish private property for the producer, but gives him individual property based on the acquisition of the capitalist era: i.e., on cooperation and the possession in common of the land and of the means of production.”

Essence and Appearance

_____Hegel

__________Logic II Essence

_____Marx

__________Capital III

“‘all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things coincided’”

Universal—————————-Particular————————–Individual

(Abstract Universal)——————————————————-(Concrete Universal) (Totality)

_____Hegel

__________Logic III The Concept – Subjectivity – Concept

_____Marx

__________second outline of Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

I. Universality:

1. (a) The emergence of capital from money.

(b) Capital and Labour . ..

2. Particularizing (Besonderung) of Capital:

(a) Capital circulant, capital fixe; Turnover of Capital.

3. The Individuality of Capital; Capital and Profit;

Capital and Interest. Capital as value, distinct from

itself as Interest and Profit.

II. Particularity:

1. Accumulation of Capitals.

2. Competition of Capitals.

3. Concentration of Capitals .. .

III. Individuality:

1. Capital as Credit.

2. Capital as Stock-Capital

3. Capital as Money Market. In the Money Market Capital is posited in its Totality.

note also the importance of the category of Totality for Lukacs

Alienation

_____Hegel

__________The Phenomenology of Spirit – Self-alienated spirit: Culture

“the Spirit whose self is an absolutely discrete unit has its content confronting it as an equally hard unyielding reality, and here the world has the character of being something external, the negative of self-consciousness. This world is, however, a spiritual entity, it is in itself the interfusion of being and individuality; this its existence is the work of self-consciousness, but it is also an alien reality already present and given, a reality which has a being of its own and in which it does not recognize itself.”

_____Marx

__________Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts

(the concept of Alienation is strongly related to that of Exploitation predominant in later works)

State

_____Hegel

__________Elements of the Philosophy of Right

__________Philosophy of Mind

_____Marx

__________Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right

History

_____Hegel

__________Lectures on the Philosophy of World History

“The History of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of Freedom”

_____Marx

__________The German Ideology

__________Preface to Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

Cyclical Presentation of the Theory

James D. White, in Karl Marx and the Intellectual Origins of Dialectical Materialism, observes that

____for Hegel,

“Each series or cycle of categories contained three elements corresponding to the moments of Universality, Particularity and Individuality which made up the Concept itself. The pattern was repeated from the initial rudimentary categories to Hegel’s entire system of philosophy. In this way Hegel adhered to the principle of Speculative philosophy that what was true of the system as a whole should be true of its constituent parts. And since the moments of the Concept progressed from Abstract Universality through Particularity to concrete Universality, the movement of the Concept was cyclical; it returned to its point of departure. This cyclic character pervaded all levels of Hegel’s system.”

and, regarding Marx,

“The cyclical method of exposition, Marx believed, corresponded to the actual working of the capitalist system. In fact, many of the movements he described were cyclical, since they concerned the circulation of money or commodities, or cycles of reproduction and accumulation.”

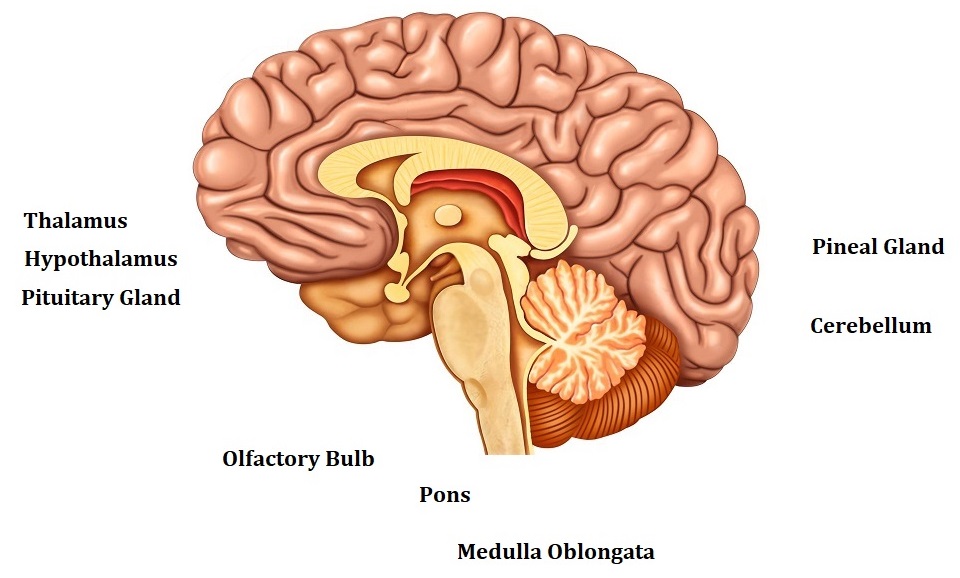

Some Notes on Hominization

From Woolfson – The Labour Theory of Culture

Bipedalism / Upright walking

Hands freed

Tools and Tool-making

Diet – high protein

Language

Social being – socialists tend to emphasize co-operation rather than competition as our most fundamental social intra-species nature – also note that many species are social

Brain size

Consciousness

[There is also an argument that bipedalism left a lot of space in the head for an expanded brain.]

High level of flexibility of human consciousness and social practices.

Perhaps unpredictable conditions, e.g. climate, necessitate flexibility.

__________________________________________________________________________

“One can distinguish man from the animals by consciousness, by

religion or by anything one likes. They themselves begin to distinguish

themselves from the animals as soon as they begin to produce their

means of subsistence, a step required by their bodily constitution. By

producing their means of life men indirectly produce their material

life itself …” Marx and Engels – The German Ideology

But 1) do no other animals produce their means of subsistence, and 2) in what sense do hunter-gatherer societies “produce” their means of subsistence, apart maybe from cooking? According to Wikipedia, hunter-gatherer societies have dominated for 90% of human history.

Relatedly, marxists often talk of “conscious labour” as the distinguishing feature of humanity. Here, I would suggest that it is the concept of consciousness that is doing all the heavy lifting in distinguishing humanity from other animals, but “labour” as central to man, his essence, has a pleasing ring to marxist ears. Without the adjective “conscious”, “labour” can be attributed to animals or indeed plants.

(Personally, I would attribute consciousness to many animals, but hold that human beings have a higher level of consciousness than animals.)

I do not wish to dispute the importance of labour to human nature, and I recognize that practice and activity are bound up with our nature, and with aspects of it such as (our level of) consciousness, and language. Marx is surely right, in the Theses on Feuerbach, to imply that philosophy has a tendency to emphasize only the contemplative aspect of our consciousness, and forget the practical or active side.

Nietzsche, in On the Genealogy of Morality, would have us be aware that “the origin of the emergence of a thing and its ultimate usefulness, its practical application and incorporation into a system of ends, are toto coelo separate”, and I think such a consideration applies to our level of consciousness.

Clarifying this philosophical anthropology is important to assessing the relevance of marxism to environmental and ecological concerns.

Continue reading